LANSDALE – Dr. Frank Boston, the physician who founded the hospital that today is Central Montgomery Medical Center, found his way to Lansdale in 1931 as the result of a camping trip and a broken leg.

A World War I veteran with a practice in Philadelphia, Boston enjoyed camping on the banks of the Perkiomen Creek, a summer respite from the city’s heat and humidity.

On one of these outings, the doctor was summoned to assist a man from Lansdale who had broken his leg. While treating him, the two began a friendship that eventually led Boston to open an office in the Dresher Arcade building on West Main Street.

It was the beginning of a long, distinguished medical career that led Boston to establish Elm Terrace Hospital and form the Lansdale First Aid Corps, which later became the Volunteer Medical Service Corps.

The life and times of Boston will be the subject of a Lansdale Historical Society Community Program Tuesday at 7:30 p.m. at the Lansdale Parks and Recreation Building, Seventh Street and Lansdale Avenue.

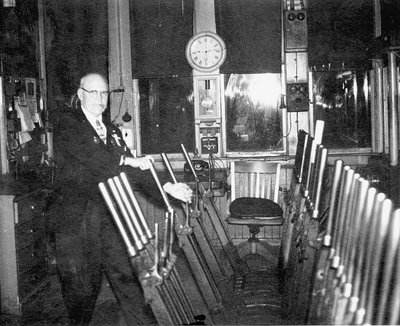

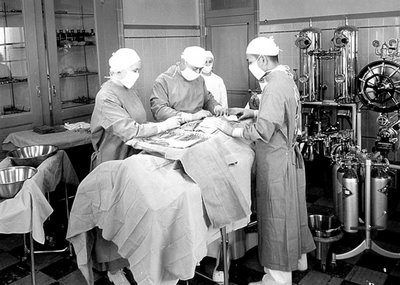

The show, narrated by the society’s Dick Shearer and Steve Moyer, will feature more than 100 images of the doctor, his hospital and the medical corps, which is celebrating its 75th anniversary this year.

“When he first came to Lansdale there’s no question that Boston was looked upon as an outsider, especially by some of the other doctors who probably feared losing business,” Shearer said.

“He stepped very lightly at first, but within three years he had the medical corps up and running and the hospital followed closely behind. In both cases he used his own money – some from his military bonus – to fund the efforts.”

Elm Terrace had a humble beginning. Boston rented, then bought, a house at Seventh and Broad streets and converted it into an 11-bed facility.

Within two years, he purchased another house on the same corner as more and more patients were brought in.

Then in 1941, he sold it to the community so that it could be run as a nonprofit facility. In 1953, it was renamed North Penn Hospital at the start of a major expansion project.

“Most people around here who remember Dr. Boston speak of him in exemplary terms,” Shearer said. “Not only was he considered an outstanding surgeon, but he often gave freely of his expertise, especially to those who needed an operation but could afford it.

“There are countless stories of him performing surgery without compensation or offering other medical services where he would refuse payment. This was especially true during the Depression and immediately after World War II, when money was hard to come by.

“He is said to have operated in dimly lit farmhouses when patients could not be transported. And there are stories of him performing surgery on animals when a veterinarian wasn’t readily available.”

The medical corps was a reflection of his Army experiences. From the very beginning, his Lansdale unit trained with military precision and a loyalty to the unit developed that carried from generation to generation. It was the only emergency and rescue squad of its kind at the time.

For all of his accomplishments there is another side to Boston’s story. Because he had non-Caucasian facial features, it was assumed by some that he was in part African-American.

According to Shearer, Boston speculated that his mother, who came from Canada, was part Native American. Whatever the case, it was cause for rumor and unspoken discrimination in the predominately white North Penn area of that era.

Evidence of this is the monument in his honor placed on the corner of the First Baptist Church Property at Seventh and Broad Sts., where the original hospital once stood.

According to Shearer, after Boston was diagnosed with bone cancer in 1958, a group of his supporters lobbied to have a portrait of him hung in North Penn Hospital.

The board of directors refused and a public fundraising campaign was established to build the memorial across the street, where his detractors had to look at it when they entered or left the hospital.

“Unfortunately, it wasn’t built until after he passed away in 1960,” Shearer added. “But it’s another important chapter of his legacy that is still talked about today.”

Tuesday night’s program is free and open to the public, but donations are appreciated. For more information, call the society at (215) 855-1872.

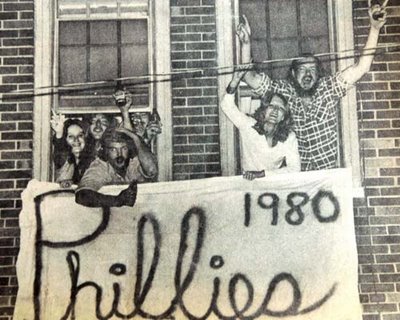

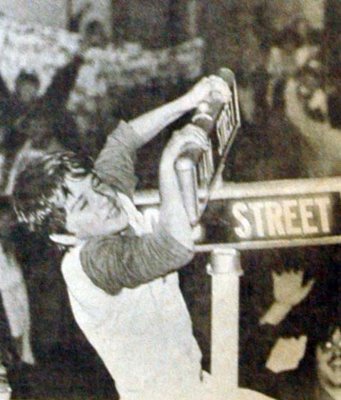

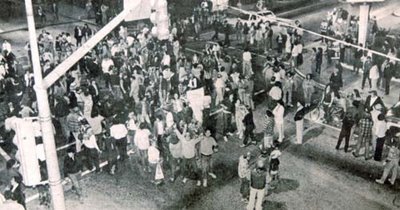

These photos were taken by Reporter photographers Bob Martin and Geoff Patton. Patton is currently the Chief Photographer at the The Reporter.

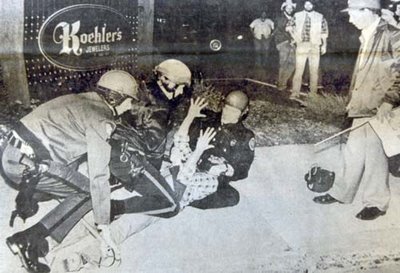

These photos were taken by Reporter photographers Bob Martin and Geoff Patton. Patton is currently the Chief Photographer at the The Reporter. According to the Reporter on October 22, 1980, one of the officers injured while subduing revelers was 23-year-old Joseph McGuriman, now Lansdale's police chief.

According to the Reporter on October 22, 1980, one of the officers injured while subduing revelers was 23-year-old Joseph McGuriman, now Lansdale's police chief.

RSS

RSS